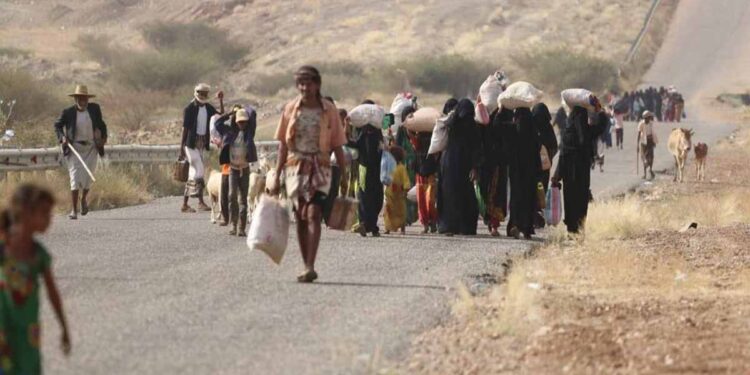

Some 172,000 Yemenis have been displaced during 2020 due to the years-long bloody conflict across the country, the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) announced in a report yesterday.

“Since the start of 2020 until 26 December, 28,659 families, representing 171,954 Yemenis, have been displaced from their homes due to several factors, mostly the country’s raging conflict,” IOM said.

IOM pointed out that “82 percent of the displacement was due to the conflict, while another 13 percent were due to natural disasters, especially in the governorates of Ma’rib, Al Hudaydah, Al Dhale’e, Taiz, Al Jawf and Hadramout.” It added that the remaining five per cent were due to “economic and health conditions caused by the outbreak of the novel coronavirus.”

“Yemen’s official unit for the Internally Displaced People (IDPs) in Marib has recorded 54,400 displaced people during the period from 20 August to mid-November,” the UN organisation added, noting that the Houthis’ recent military escalation against Marib was the “main reason for the new displacement wave.”

Since 2014, war has driven poverty in Yemen from 47 percent of the population to a projected 75 percent by the end of 2019, according to the UN, which has classed the situation “the world’s worst humanitarian crisis”.

Famine in Yemen

Impoverished Yemen would be at risk of a devastating famine should the outgoing Trump administration push ahead with a move to designate the country’s largest rebel group as a terrorist organisation, the UN’s aid chief warned.

Mark Lowcock, UN under-secretary-general for humanitarian affairs, said food imports to the impoverished Arab country plummeted by a quarter in November after US media quoted officials as saying that President Donald Trump planned to label the Iran-aligned Houthi movement as a foreign terrorist organisation before his term ended.

Food import numbers had not improved in December, Mr Lowcock added. Aid groups say that Yemen, where a multi-sided war has raged for nearly six years, faces the world’s worst famine in decades. “There’s a chilling effect of the [terrorist] designation . . . that risks undermining imports of food and becomes the final straw that tips the country into not just a small famine, but a large one,” Mr Lowcock told the Financial Times in an interview.

“The question is whether it’s going to become a large famine or a truly huge famine on a scale the likes of which the world has not seen since 1m people lost their lives in Ethiopia in the 1980s.”