The Egyptian regime’s ongoing use of executions as a weapon against political dissent was taken up in an online seminar organised by Arab Organisation for Human Rights in the UK (AOHR UK) on Thursday, 7 April.

Panellists included Italian member of parliament Massimo Ungaro, former US assistant attorney general Bruce Fein, the chair of Egyptians for Democracy, head of the Egyptian Revolutionary Council and a founding member of the Brussels Initiative Dr Maha Azzam, professor of political science and international affairs at American University’s School of International Service William Lawrence, and associate professor of political science at Long Island University Dalia Fahmy.

They discussed not only the horrifying expansion of the use of executions by the al Sisi regime, but also the reasons behind the growth of such repression and what governments, international institutions and also human rights campaigners can do to challenge such abuses.

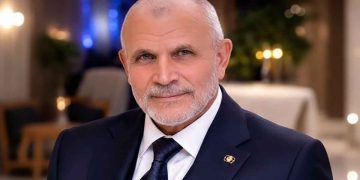

The seminar was chaired by Nasim Ahmed, a researcher at the Middle East Monitor news website. He began by noting the “great horror and shock” of witnessing “Egypt’s slide towards repression and authoritarianism” since 2013.

He said: “Over the past eight years in particular we’ve seen the number of dissidents in executions has sky-rocketed… and shows no signs of abating. Egypt now ranks among the worst countries in terms of executions around the world.”

Ahmed added that unlike China and Iran, which also execute huge numbers of dissidents every year, Egypt was a key ally of the United States, making it “deeply entrenched in the system”.

The first panellist to speak was Massimo Ungaro, a member of the Italian Chamber of Deputies for the Italia Viva party. He noted that violations of human rights in Egypt were happening at a faster pace than even under former dictator Hosni Mubarak, which led Italian politicians to act. This concern was also spreading to some in the European Parliament. “There have now been at least four resolutions in the European Parliament condemning Egypt,” he said.

“Egypt is an important ally for Western countries,” he added, but “that should not in any way exempt us from condemning” the regime’s abuses.

He spoke about the need to find ways in which European politicians could punish the al Sisi regime without harming the people of Egypt, who are themselves already the victims of his military dictatorship. “That’s why Italy suspended the Italian ambassador to Egypt for a year and a half,” he noted.

He said, however, that European politicians needed to do more. “The European Commission has discussed the matter but has not offered any practical decisions or any practical initiatives.”

Former assistant US attorney general Bruce Fine was next to speak. He began by noting how the international community, in general, was opposed to the death penalty. In making the point, he noted: “The International Criminal Court, which tries crimes of crimes including genocide, does not have the death penalty as a punishment.”

“In the case of al Sisi the death penalty and the charade trials need to be examined in a little broader light to do justice to the heinousness of the offenses to humanity, if you will,” he added.

He argued that, while imperfect, the most likely route towards bringing justice against al Sisi was the International Criminal Court. He said: “It seems quite clear that he has selected all critical dissidents to crush, to destroy. Political opinion, in his view, is a valid criteria to denying someone any human right including the right to live, and that kind of blanket opposition, blanket violence, blanked oppression is a crime against humanity under Article 7 of the International Criminal Court and it seems to me that is a forum that needs to be pursued…”

Dr Maha Azzam followed, and spoke about the importance of meetings such as this with figures outside Egypt, due to the horrific levels of oppression against anyone daring to speak out in Egypt itself.

She continued: “We need a moratorium on executions because there is an absence in the rule of law and this regime.”

She charted al Sisi’s route to power, from “the back of a tank” in the 2013 coup. “He hijacked Egypt’s nascent and democratic experiment.”

Dr Azzam argued that the use of executions was part of a wider campaign to silence opposition to the military dictatorship. “The political context is that of a military coup against a democratic process that did not last more than a year before the military intervened once more to maintain its power and privilege, which it has exercised since 1952,” she said.

“The Sisi regime is probably one of the worst dictators that Egypt has ever seen, and he is supported by the West and by regional powers, and is allowed to continue.”

She noted the role of the west in supporting al Sisi’s repressive regime. She said: “My message here is that the outside world, particularly the United States and democratic governments, are enabling this dictator so that the Egyptian people cannot move.

“Not only can they not move, they cannot breathe. Egypt is a republic of fear and Egyptians today are fearful in every move they make. And every person who raises their voice knows that there is an enormous price to pay, whether an actor, whether a journalist, whether a worker, whether a judge…”

Dr Azzam noted how the military was now in control of large sections of the economy, and that western governments could therefore use sanctions to punish it.

“Unless sanctions are carried out against this regime, different sorts of sanctions so that the red carpet treatment is not given to his generals and to his coterie of supporters and ministers so that action can be taken against the Egyptian people by him, then I believe that history will record that both United States and democratic powers not only enable Sisi, but were ultimately complicit in the death and torture of Egyptians,” she said.

William Lawrence, professor of political science and international affairs at American University School of International Service, agreed with those who spoke before him, also noting his disappointment at the lack of organised resistance to the Egyptian regime.

“The situation in Egypt is dire,” he said. “The position of the international community is weak and feckless, and a lot needs to be done.”

He spoke of the problems of using the ICC as a tool to beat Sisi, especially as the US want not even a member itself – which has been part of the problem in the west challenging Vladimir Putin over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

He said: “We need a reordering and rethinking of the international community, which is not properly set up in a number of ways right now, to address these types of issues.”

“In terms of the US position, the withholding of $130 million of aid on human rights grounds in January is OK, it’s a step, it’s an action the Egyptian government hates it, so in that respect it’s a good thing.

“US levels of assistance to Egypt are fixed by the Camp David Accords. But there’s a whole lot more that can be done through Congress to withhold larger amounts for longer periods to cause more pressure and more heartburn in Cairo than is currently the case. “

He added: “I just don’t think that the pressure on the Egypt issue has been strong enough. There needs to be a cost to the US government, a cost to the UN and a cost to the Gulf countries, among others, for the price of doing business for the price of the status quo and the cost right now, reputationally and politically, is not high enough, and it needs to get larger.”

Lawrence added that the problem with the death penalty in any society was that “in most cases, even in democratic societies, it’s misapplied”.

“And so in the context like Egypt, where it’s completely politicised and arbitrary, and atrocious and a war crime, it’s ten times the problem that it already is in the societies that use it democratically.”

Dr Dalia Fahmy, associate professor of political science at Long Island University, gave a passionate and devastating assessment of the current situation in Egypt.

She began with a call for urgency. “We need to talk about the strategic use of timing in terms of mass death sentences but also executions at the moment to chill political activity or what could potentially be social activity towards the end of the month and going into this summer.”

Dr Fahmy noted that there are currently 60,000-80,000 political prisoners in Egypt, so many that “the regime has had to build between 16 and 23 new prisons to handle the overflow”.

She also spoke of the difficulties in even knowing how many people have been executed by the regime: “There have been at least 521 executions that we know of, and according to figures, this could be even more than that, because we are not counting here extrajudicial killings.”

Changes to the law and constitution by the regime of al Sisi vastly broadened those at risk of execution for “terrorism”.

She said: “Defaming the state falls under the terrorism law. If you have between 4-5,000 Twitter followers, you are seen as a social media influencer, a news outlet, if you will. And so if you say something outside of the state narrative, you can be held and tried under the terrorism law and even be liable to these to these sentences.”

The mass trials, she said, were illegitimate and designed by the regime to terrify the population into obedience.

“These trials that lead to death sentences and executions, we all know are now sham trials,” she said.

“Accusing, for example, 90 people for the death of a single individual and then, without due process, trying them and calling for their execution. There are individuals who are being tried in cases where they were actually imprisoned when the crime was committed.”

She continued: “The culture and the state of fear that has been created in Egypt is unlike anything we’ve seen in the past.

“The entire narrative on democratisation throughout the world is no longer about good governance, transparency, human rights, accountability.

“It is simply about not killing with impunity.”